Far from merely being a component of music theory, the Circle of Fifths is the key to unlocking the mysteries of Western music. With just one easy-to-memorize diagram, you’ll not only be able to recall keys and key signatures, but also utilize this knowledge to transpose music, write impactful chord progressions, and compose melodies.

What Exactly is the Circle of Fifths?

The Circle of Fifths is a tool that you can carry around with you in your back pocket, or even in the back of your brain.

It’s one of those rare musical tools that is equally helpful for understanding theoryandfor applying it to practice and songwriting.

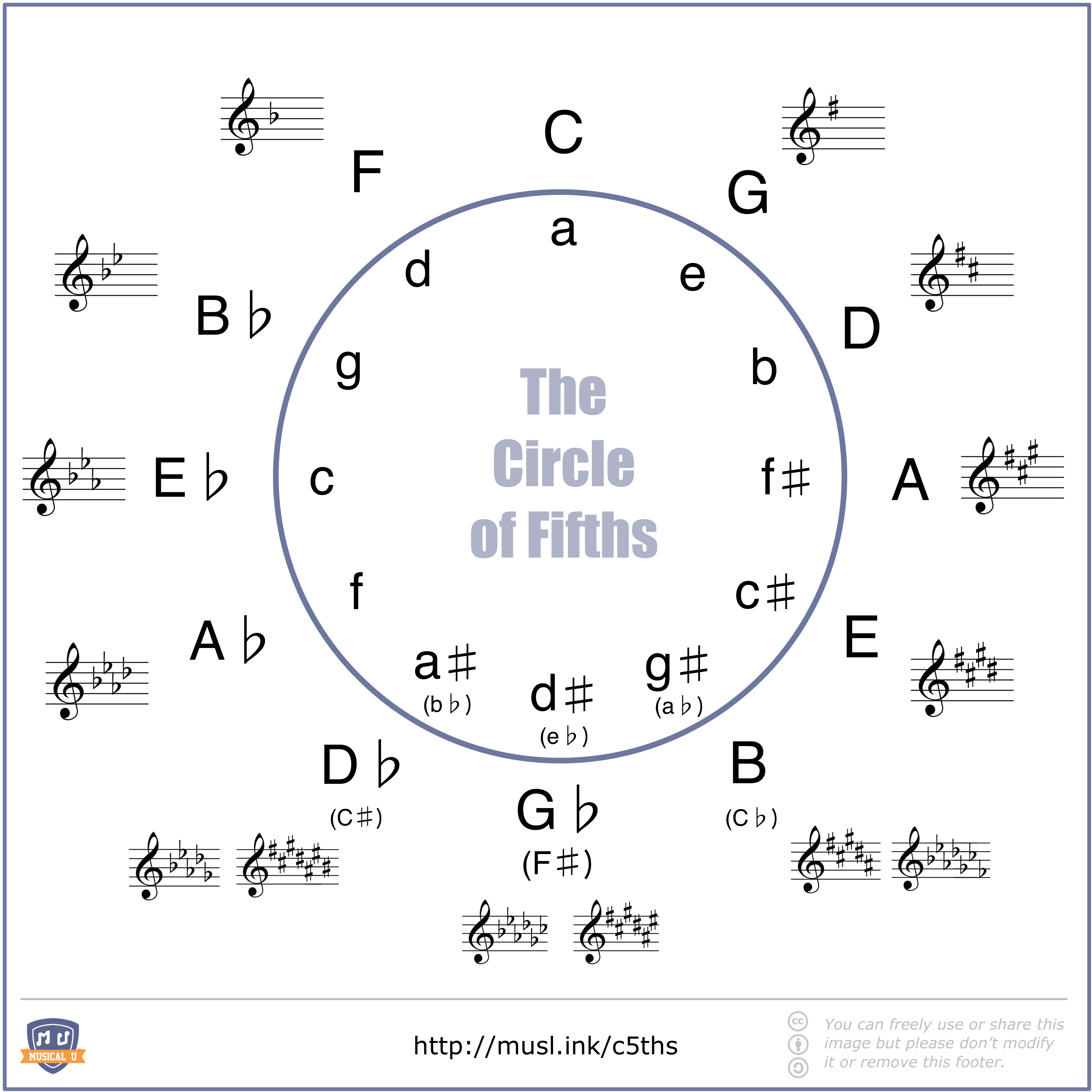

The all-in-one diagram gives you every major key, along with its key signature and relative minor, so you can gather the basic information of the key you’re playing in just by glancing at it.

Beginnings of the Circle

The Circle of Fifths has been around for a long time, though it didn’t always look like the diagram we know and love today. In the late 1670’s, Russian composer and music theorist Nikolay Diletsky wrote Grammatika, a guide to music composition with music theory in mind.

Included in his work was a rudimentary Circle of Fifths. Evidently, enough musicians and theorists caught on to its brilliance that it stuck around. With many revisions and expansions, we got the circle as we know it today.

The Building Blocks of the Circle: Keys and Fifths

Before we dive right into the Circle, let’s look at the key concepts underlying it; the two most central to understanding the circle are keys and fifths.

Keys

Every piece of music has a tonal center, a note that the music naturally resolves to. This note is given the name of the tonic, and is given the scale designation I. Another name for this tonal center is the key.

Each key will have its own key signature, a series of sharps or flats that helps maintain the quality of the key (major or minor). The key signature ensures that the tone/semitone pattern is consistent across all keys of the same quality.

For example, all major keys will have the pattern tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone-tone-semitone, no matter which note they start on!

Fifths

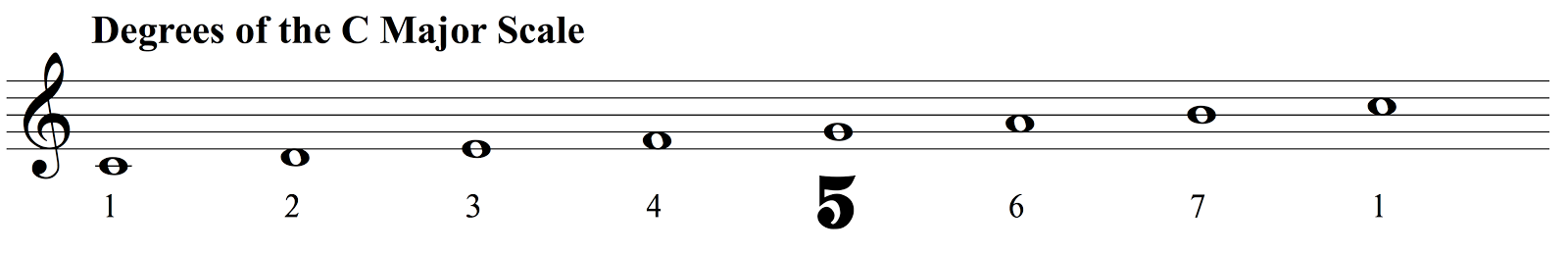

So if we have the tonal center, or the tonic as the first scale degree (I), we have seven scale degrees in total.

The fifth scale degree (V) is perhaps the second-most important one, after the tonic.

The tonic and the fifth, when played together, are referred to as a perfect fifth interval, or simply a perfect fifth. Without going into complicated physics, the basic reason it’s so “perfect” is because the interval vibrates at a pure mathematical ratio, creating a pleasant, consonant sound.

The fifth of any key can also be found by counting seven semitones up from the tonic.

The Components of the Circle of Fifths

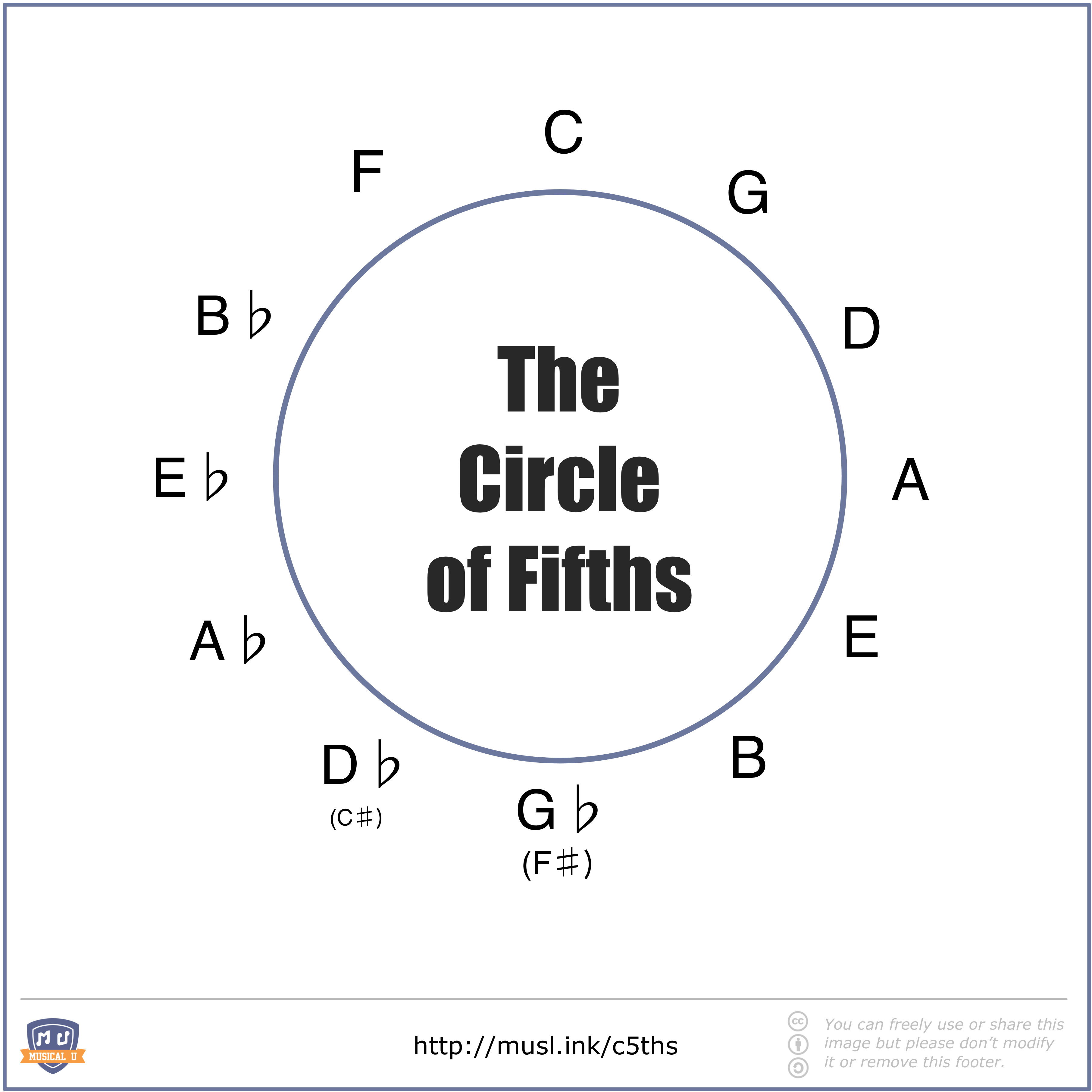

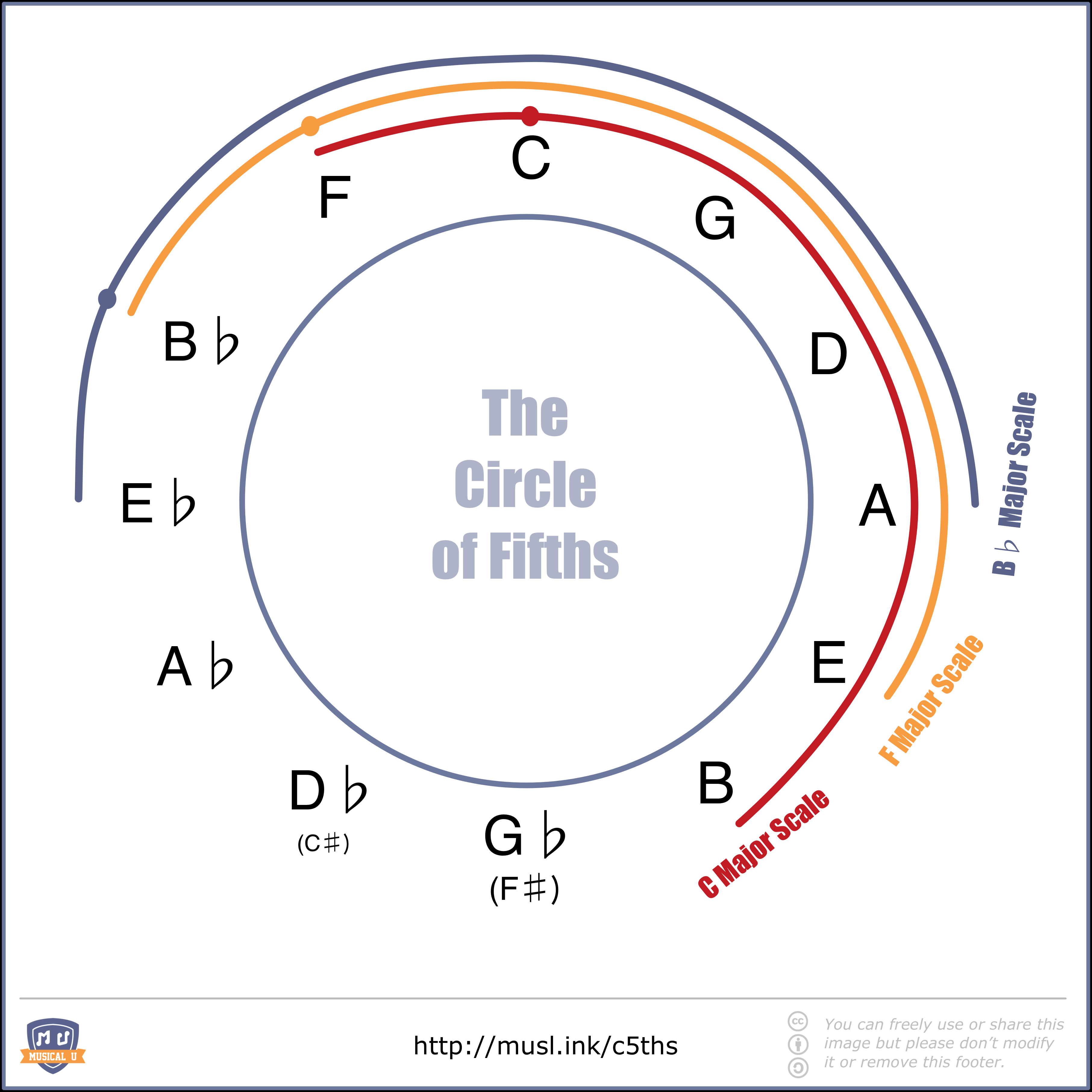

Now that we understand keys and fifths, we’re ready to take a look at the basic circle:

The circle is in fact built on perfect fifth intervals! We start with C major at “12 o’clock”, with each step clockwise being a perfect fifth above the previous note.

In fact, each station on the circle is a note and a key!

Key Signatures

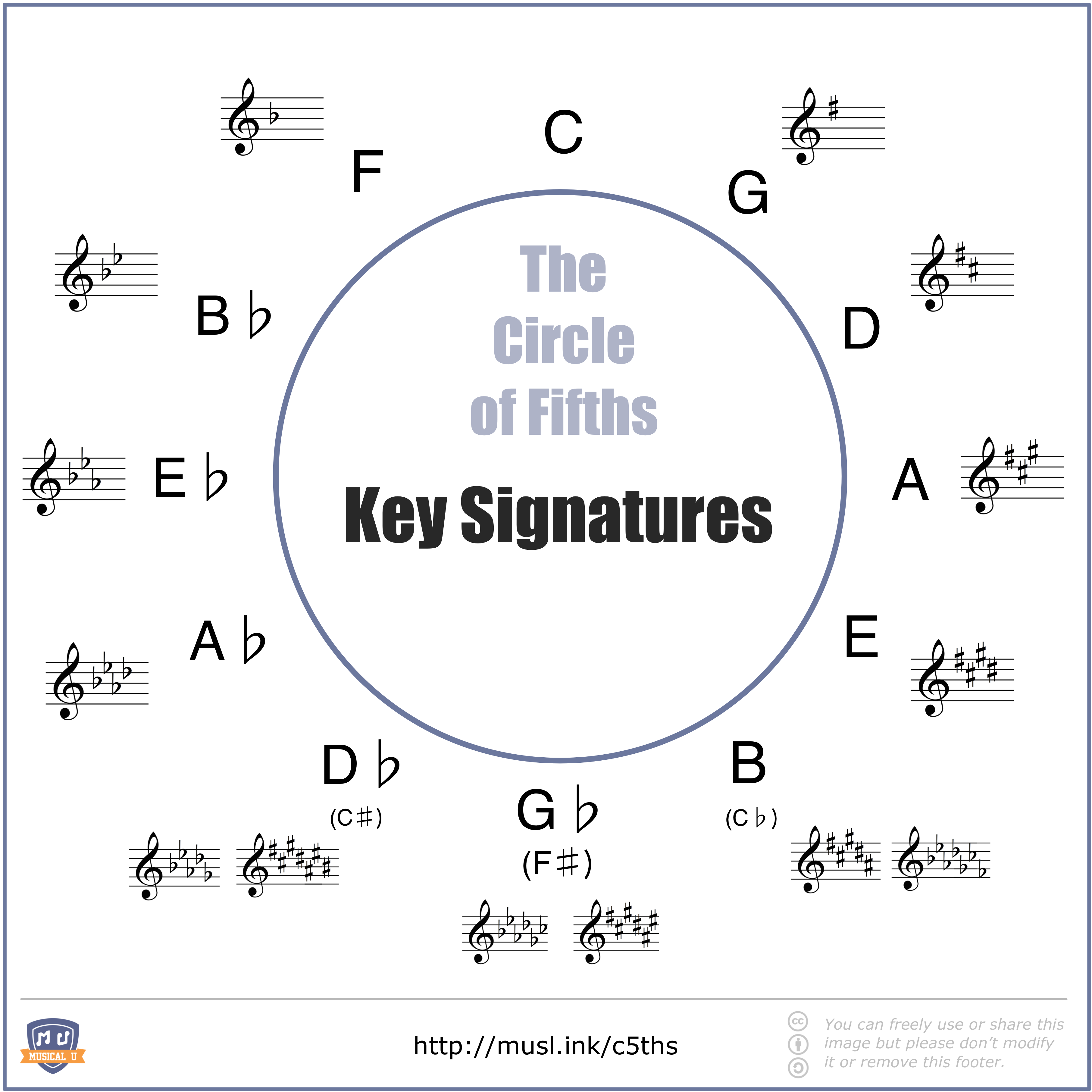

Let’s add another layer to the circle:

This gives you the major keys with their respective key signatures. Take a look; starting at C major and going clockwise, each new key has one new sharp added to it. Go counterclockwise and it’s the same, just with flats!

It looks a bit crazy, but there’s a repeating pattern to it: simply memorize the sequence F-C-G-D-A-E-B. This gives you the order in which sharps are added clockwise. Reverse this sequence to B-E-A-D-G-C-F, and you get the order in which flats are added counterclockwise.

The number of steps you take around the circle, starting at C, will tell you how many sharps or flats the key will have.

Let’s try an example by figuring out B major’s key signature.

We look at the circle and see that B major is five steps clockwise from C major, so we know we are adding sharps. Look to the F-C-G-D-A-E-B sequence to determine that B major has F#, C#, G#, D#, and A#.

Relative Minors

Now that we have the major keys and their key signatures, let’s add in the final layer: relative minors!

The good news is, this is perhaps the easiest part; most of the work has already been done for you.

The relative minor of a major key will be the 6th degree of the major scale, or three semitones down from the tonic of the major key. If you don’t feel like whipping out a keyboard or writing out scales, the circle itself can help you find all the relative minors – it practically builds itself!

Simply move three steps clockwise from the major key to find the key of the relative minor. Let’s try an example what’s the relative minor of G major?

Head three steps clockwise from G major, and you get to E. The relative minor of G major is therefore E minor.

Relative minors have the same key signatures as their parent major key, and therefore all the same notes. Also, if you’ve been paying close attention, you’ll notice that the relative minors going around the circle clockwise are also a fifth apart!

Using the Circle of Fifths

Once you have the major keys, minor keys, and key signatures that make up the circle, you’re ready to put it to good use.

In fact, you’ve already been clued into two of its uses – spotting the relative minor and key signature of any key at a glance!

Beyond the obvious, the circle has countless uses that become apparent upon closer inspection.

Building Chords with the Circle

Chords are merely clusters of notes that sound pleasant and make sense together.

We’ll focus on the most popular ones here – major, minor, and dominant seventh chords.

Major and Minor Chords

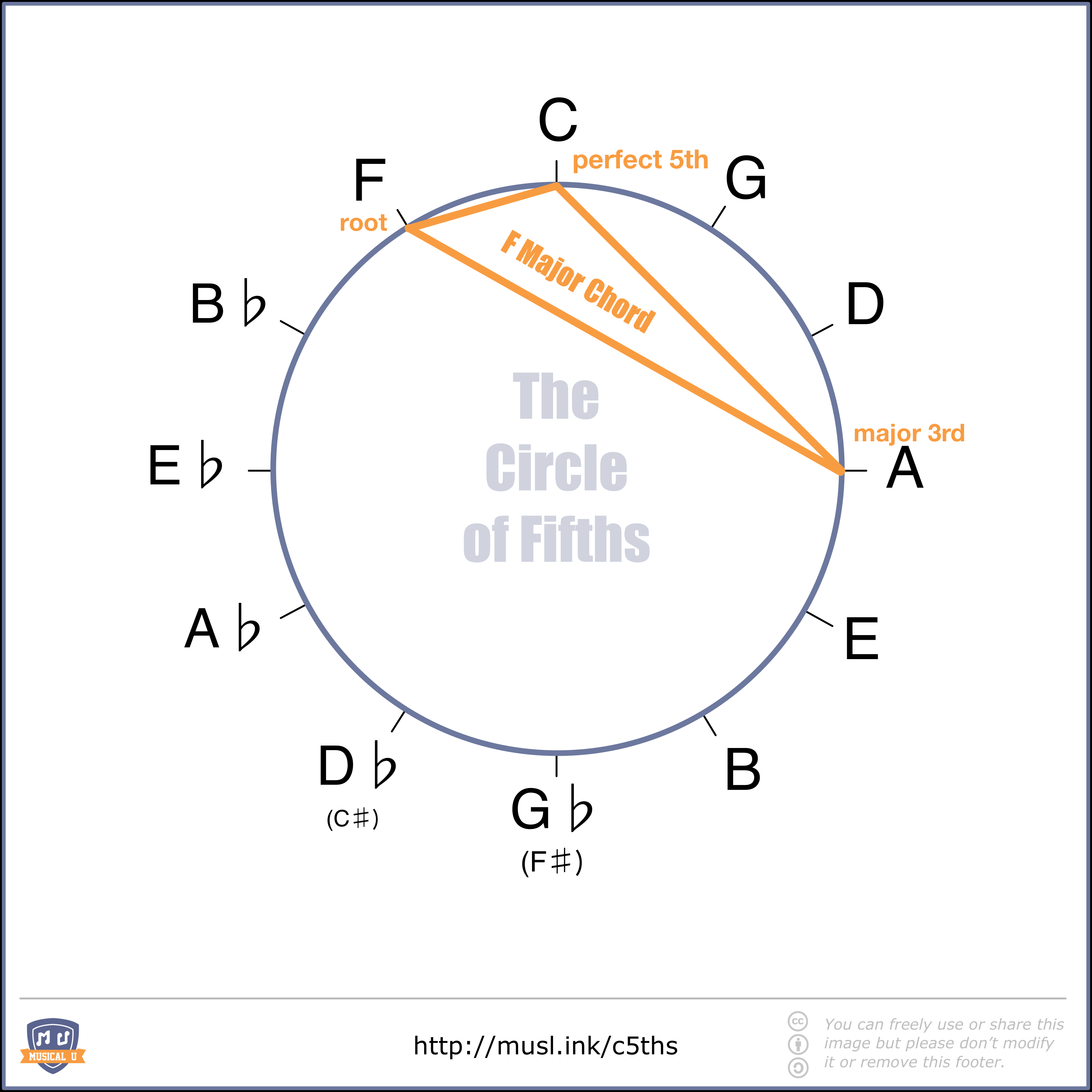

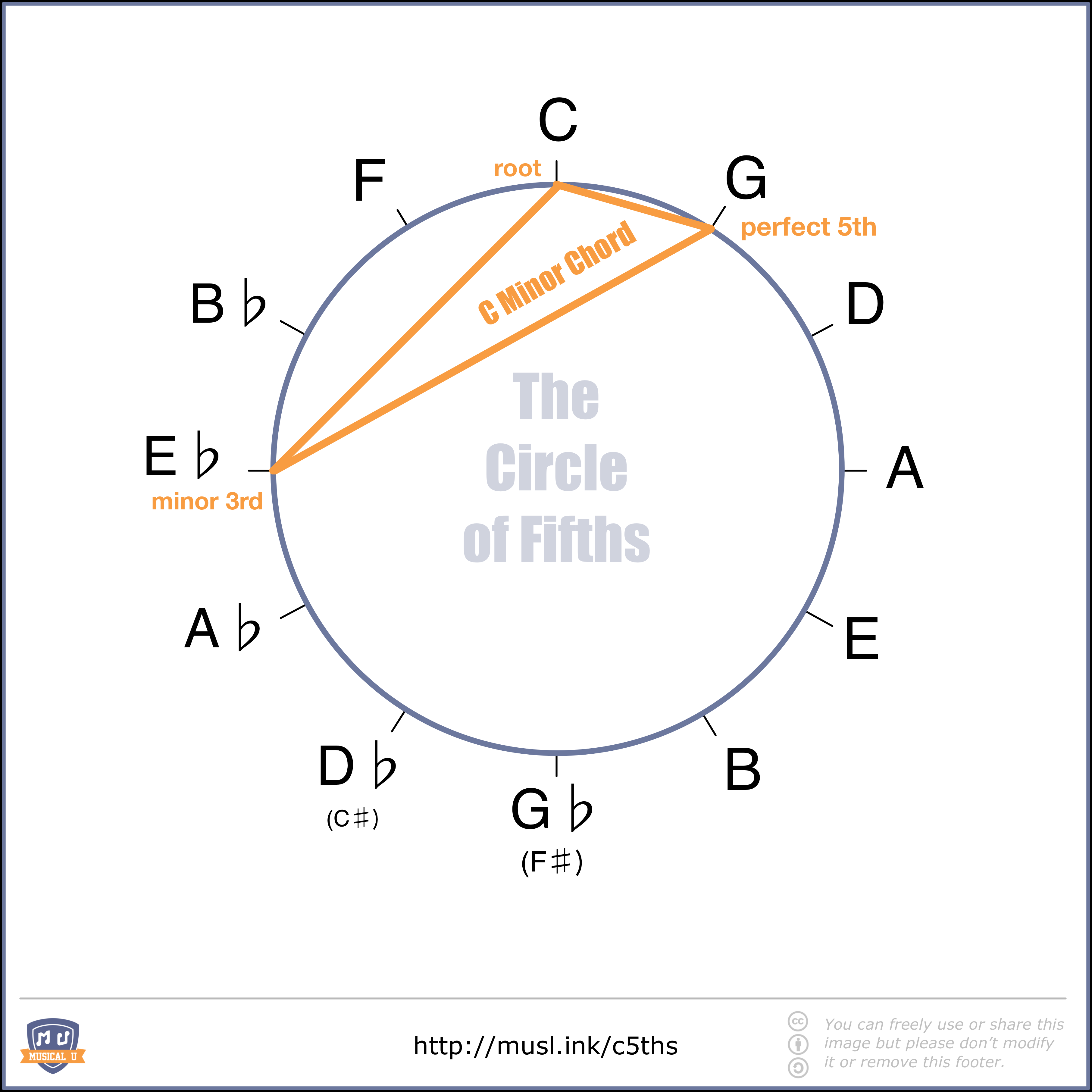

These simply consist of a root note, a perfect fifth above the root, and either a major third (for major chords) or a minor third (for minor chords).

The circle all but gives you the answer; find the fifth by counting one step clockwise on the circle. As for the third, simply count up four semitones from the tonic to find a major third, and three semitones from the tonic to find a minor third.

If you don’t want to count semitones to find your third, the circle is here to rescue you yet again! In a major chord, the major third note will be found four steps clockwise from the tonic. For example, the major third above F will be A:

As for a minor chord, the minor third will be found three steps counterclockwise from the tonic note. For example, a C minor chord’s middle note will be E♭:

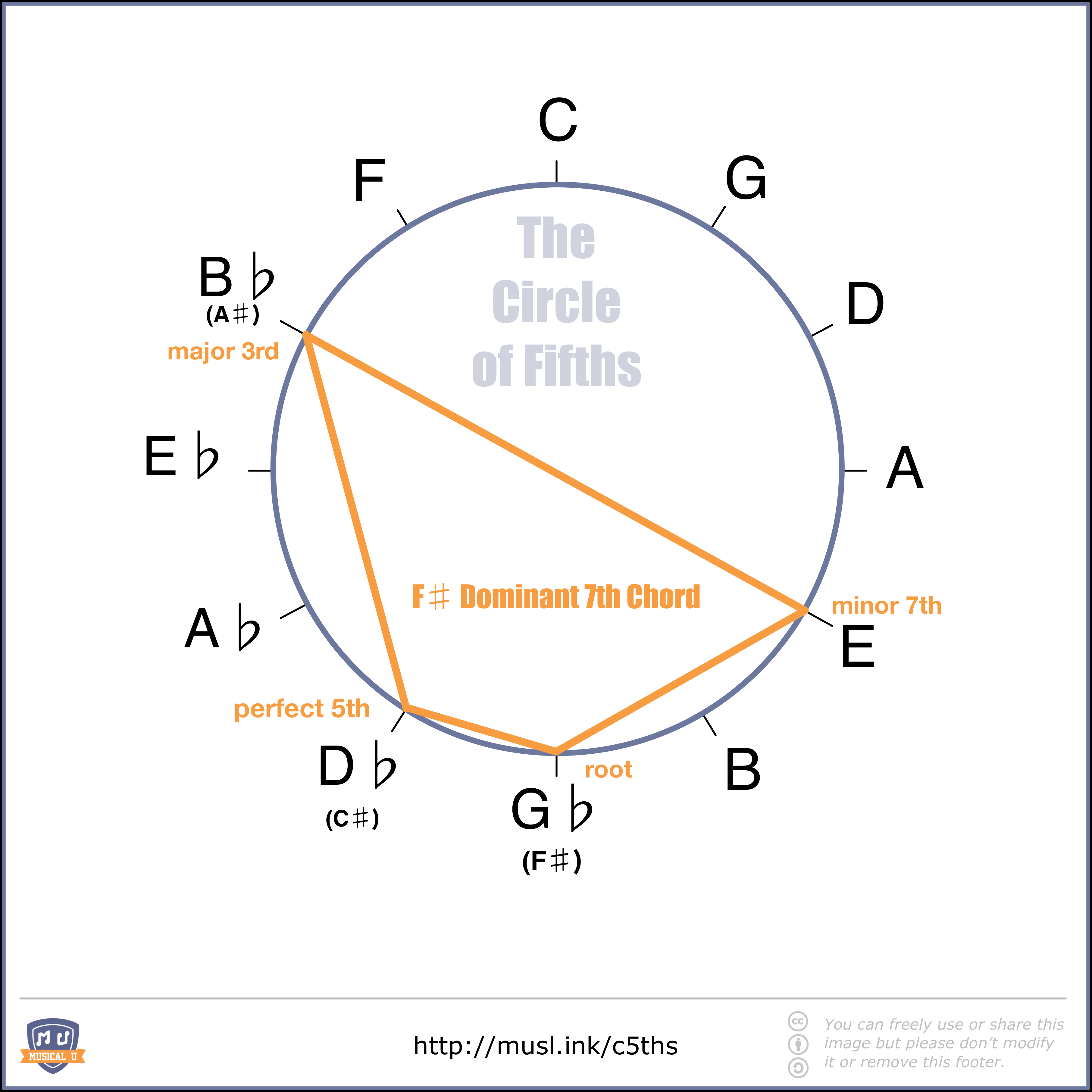

Dominant Seventh Chords

These chords are ubiquitous in popular music. They create a rich, full sound that works particularly well in jazz music.

They’re also easy to build, with the help of the circle! The dominant seventh chord is simply a major chord with a minor seventh stacked on top.

Build your major triad as you normally would. As for the seventh, watch as the circle comes to your aid again! Simply count two steps counterclockwise from the key in which you’re building the chord.

Try this yourself! Build a dominant seventh chord in F# major, and check out the diagram below to see if you got it!

Using the Circle to Play a Simple Chord Progression

A refresher: the most important note in any key is the tonic. It’s the tonal center of the music, the step that the melody will naturally resolve to.

The second-most important chords in a key are the subdominant (IV) and dominant (V). In fact, an amazing number of popular songs make use of the I – IV – V chord progression!

The circle all but shows you how to find this chord progression in any key. Pick any key as your starting point, your tonic. The subdominant (IV) will be found one step counterclockwise to the tonic, while the dominant (V) will be found one step clockwise. For example, if B major is your tonic, E is your subdominant (IV), and F# is your dominant (V).

You can now build your I, IV, and V chords, also using the circle. From there, go ahead and play around with those chords – you’ll be surprised with how many amazing tunes you can build with just those three!

The Circle of Fifths for Songwriters

Beyond simple chord progressions, the circle has a sneaky way of telling you which chords work together, helping you build chord progressions and melodies.

As a general rule, chords that are close together on the circle will sound good in a progression. Why? Because of the order in which they’re arranged, and the fact that accidentals are added stepwise, each key shares 6/7 of its notes with both its neighbours!

Try building a chord progression that moves around the circle from one “station” to the next; you’ll find that the progression will sound pleasant and consonant, and that you can easily write a melody on top of it.

For something with a little more edge, or some dissonance, try leaping across the circle to a less-related key! You can use this for dramatic effect, to signal a shift-in-gears in the music. You can always find your way back to your tonic after, by continuing your path around the circle.

Jump into the Circle!

It takes some memorization and understanding, but once you understand the mechanics and applications of the Circle of Fifths, it equips you with both theoretical knowledge and compositional ideas.

Before you know it, you’ll start seeing your own patterns in the circle; cheats and tricks to help you see the relationships between notes, chords, and keys.

Now that you’re armed to the teeth with the mechanics and applications of the Circle of Fifths, print (or draw out!) your own version, and experiment with creating your own melodies and chord progressions!